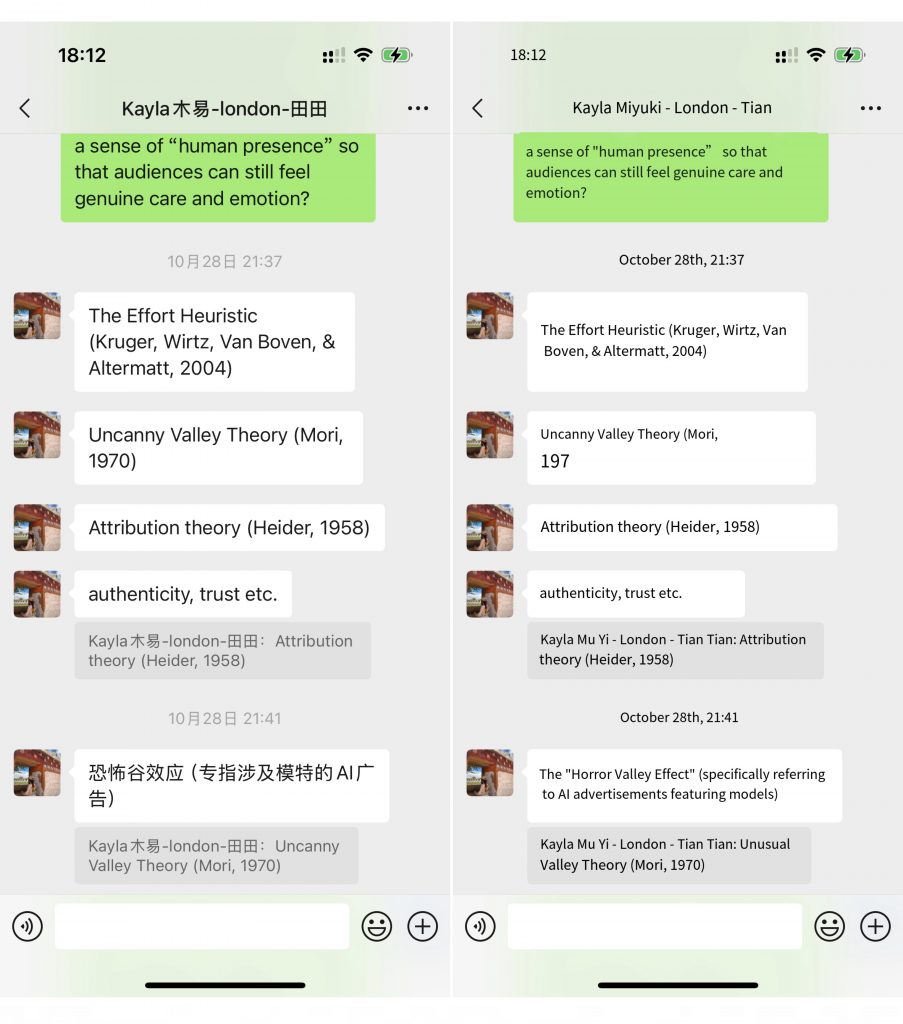

After clarifying my methodological direction, I conducted an expert interview with a psychology researcher whose work focuses on emotion, empathy, and perception.

This conversation offered deep insights into how people emotionally interpret AI-generated visuals — not purely through what they see, but through what they believe the image represents.

The discussion also reaffirmed how my previous findings in Unit 3 (safe zone, sensitive zone, and trust through co-creation) align with cognitive psychology, forming a theoretical bridge for my upcoming Intervention 4.

1. Emotion as Cognitive Interpretation

The psychologist emphasized that emotion is a cognitive process of interpretation, rather than a spontaneous reaction.

When viewers look at an AI-generated image, their response depends on the intention they attribute to the creator.

If they sense human involvement and effort, empathy emerges; if they sense automation or deception, they detach emotionally.

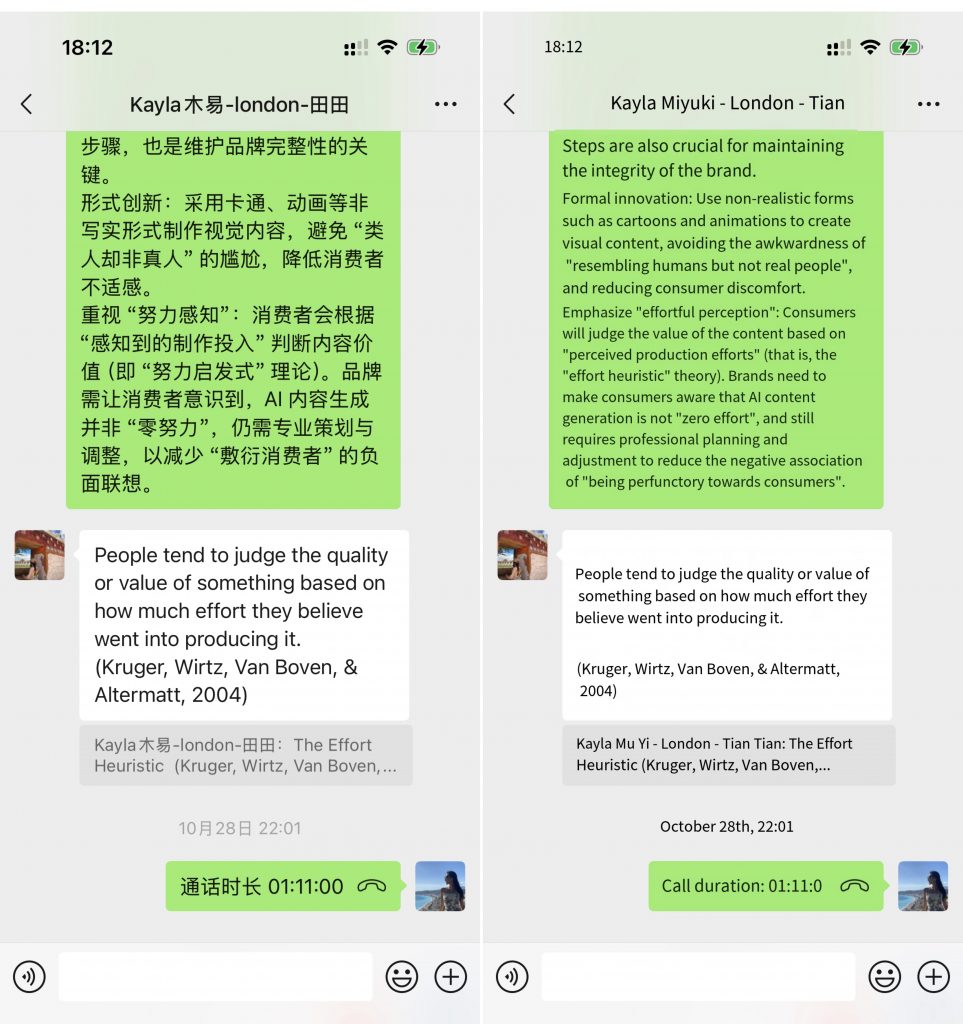

This idea echoes the Effort Heuristic Theory — audiences value what they perceive as “made with care.”

Hence, AI design should not simply aim for perfection but should communicate human intention and emotional labour behind the visuals.

2. Authenticity, Familiarity, and Trust

From a psychological lens, authenticity and trust are built on familiarity.

Human brains are trained to recognize subtle cues of life and intention.

When these cues disappear — as in many AI-generated visuals — people experience uncertainty and emotional distance.

The expert linked this to Attribution Theory: audiences constantly infer motives.

If they perceive honesty and transparency, they reward the brand with trust; if they sense manipulation or concealment, they withdraw.

3. The “Uncanny Valley” and Perceptual Sensitivity

A major point from the interview was the Uncanny Valley Effect — the discomfort people feel when something looks almost, but not fully, human.

This aligns precisely with my Unit 3 results:

AI-generated backgrounds were widely accepted (Safe Zone), but human models triggered unease (Sensitive Zone).

The expert explained that this discomfort is not just aesthetic but neurological — our brains detect inconsistency in skin texture, micro-expressions, and light logic.

Thus, in design applications, AI should stay within perceptual comfort zones, or intentionally stylize human figures to avoid false realism.

4. Audience Co-creation as a Mechanism for Repairing Trust

The psychologist validated my previous co-creation experiments, suggesting that participation itself repairs emotional distance.

https://24042236.myblog.arts.ac.uk/wp-admin/post.php?post=138&action=edit

When audiences contribute to AI creation (e.g., by suggesting prompts or evaluating visuals), they experience a sense of agency and ownership, which enhances empathy.

However, she also reminded me that deep interaction may not be feasible for mass-market brands.

Reflecting on this, I realized that in large-scale practice, lighter-weight forms of interaction (such as feedback, visual selection, or short surveys) can still extend emotional co-creation..

This perspective confirms that co-creation can function as a psychological trust-repair mechanism, transforming passive observation into relational connection.

5. Transparency and the Ethics of Perception

The expert emphasized that transparent disclosure is essential to sustaining trust, helping brands preserve ethical integrity and emotional credibility.

She pointed out that even if AI-generated content lacks full authenticity, proactive disclosure and openness can still signal to audiences that the brand is acting honestly and respectfully, thus maintaining trust. https://24042236.myblog.arts.ac.uk/wp-admin/post.php?post=136&action=edit

But when AI content is presented as fully human-made, it activates moral discomfort and distrust.

This finding reinforces my theoretical model from Unit 3 — transparency works as a conditional trust factor: it may slightly reduce emotional warmth but increases integrity and acceptance.

6. Integrating Psychology into Design Methodology

Through this conversation, I began to see emotion not as an outcome but as an interactive process of empathy and meaning-making.

The expert’s explanation bridged psychological theory with my applied design practice:

- Emotion = Cognitive interpretation

- Trust = Perceived honesty + Familiarity

- Connection = Shared authorship

These principles expand my design framework from aesthetic evaluation toward human-centered emotional architecture. - AI is not merely an intelligent tool for enhancing brand efficiency — it can cultivate users’ perception and emotional experience of a brand, even shaping an ongoing, evolving human-like relationship. At the same time, AI endows the brand with a sense of vitality and agency, transforming it into a living, growing entity.

7. Reflection and Next Step

This expert dialogue reframed my understanding of emotional authenticity in AI design as a multi-layered construct:

it depends on cognitive empathy, perceptual safety, and participatory trust rather than visual realism alone.

By intentionally incorporating traces of human imperfection, clear attribution, and audience agency, designers can evoke genuine emotion even in algorithmic contexts.

These insights will directly inform my Intervention 4, which observes emotional reactions as audiences watch an AI designer and a non-AI designer create in real time.

Through this experiment, I aim to translate psychological concepts — such as the effort heuristic, the uncanny valley, and empathy cues — into practical strategies for emotionally intelligent design systems.

Key Takeaways

- Emotion is a cognitive interpretation, not a passive feeling.

- Trust is shaped by transparency, perceived effort, and honesty.

- The “Uncanny Valley” explains why backgrounds = safe zone and human models = sensitive zone.

• Co-creation offers a trust-repair pathway by giving audiences agency.

• Transparency redefines authenticity as a psychological, not purely visual, quality.

Leave a Reply