1. Theme

This intervention aims to examine the differences between AI-assisted creation and traditional (non-AI) creation in brand visual communication design — focusing on their thinking logic, creative process, and expressive outcomes.

It explores the balance between technological efficiency and brand emotional value, and seeks to identify the boundaries of AI creativity through a process of “situational dialogue.”

The experiment consists of two main stages — Independent Creation (Phase 1) and Co-Creation (Phase 2) — supported by real-time observation, discussion, and post-experiment questionnaires.

Participants:

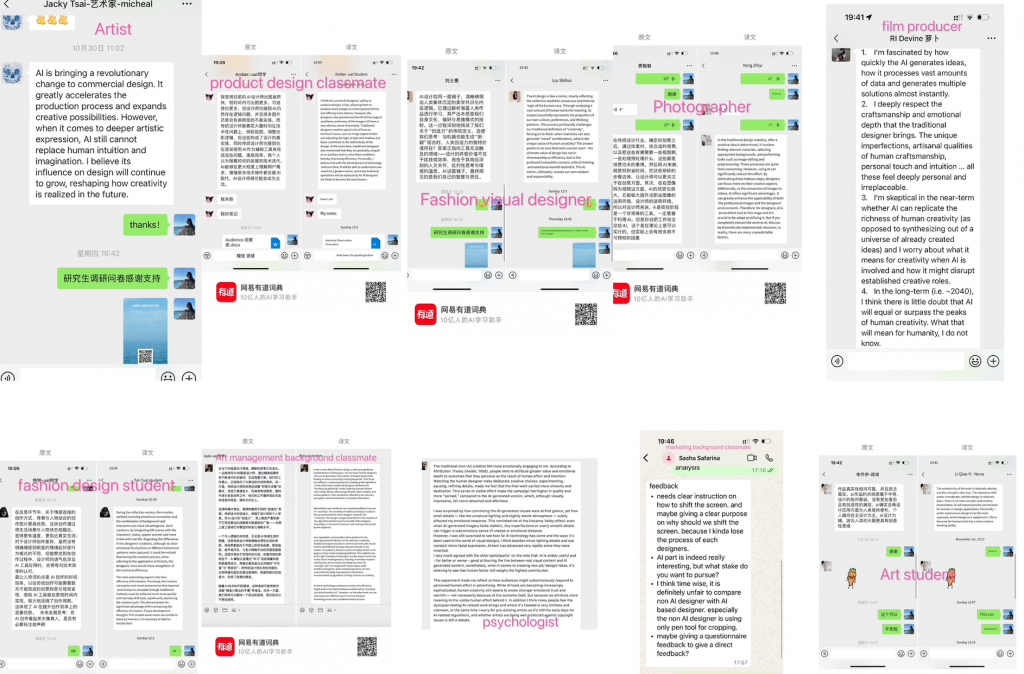

One traditional brand visual designer, one AI visual designer, the host, and 10 stakeholders interested in AI/brand design (including but not limited to art students, designers, photographers, psychologists, and marketing professionals).

2. Phase 1 — Independent Creation

Description:

The traditional and AI designers were each given around 30 minutes to complete a visual redesign for a handbag brand.

Process:

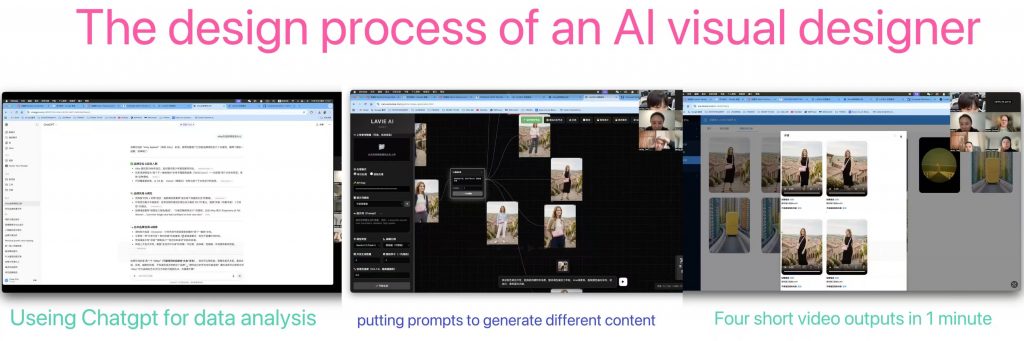

- Early stage: The traditional designer collected references and inspiration online, while the AI designer conversed with GPT to organize creative directions.

- Mid stage: The AI designer rapidly generated visual advertisements based on GPT’s analytical guidance. Within minutes, the AI produced multiple visually striking outputs with high iteration speed, which quickly captured the audience’s attention. Several participants expressed curiosity and even attempted to test the AI software themselves.

Meanwhile, the traditional designer was manually cutting and compositing images, which drew relatively limited feedback from observers. - Late stage: The traditional designer completed a poster emphasizing realistic lighting and texture refinement, while the AI designer produced dozens of still and video visuals, continuously engaging with the audience and provoking multidimensional discussions.

Phase 1 Summary:

Compared to traditional methods, AI can process and generate visuals more efficiently based on trained datasets. However, its logic and uniqueness still require human guidance and brand decision-making to avoid homogenization.

AI’s efficiency and diversity became the main focus of audience curiosity and interaction, transforming interest into emotional engagement. The results demonstrated that AI creativity offers efficiency, novelty, entertainment, and a certain level of realism.

3. Phase 2 — Co-Creation

Description:

Building on the materials from Phase 1, the traditional and AI designers collaborated to produce a new set of brand visuals and promotional content.

Process:

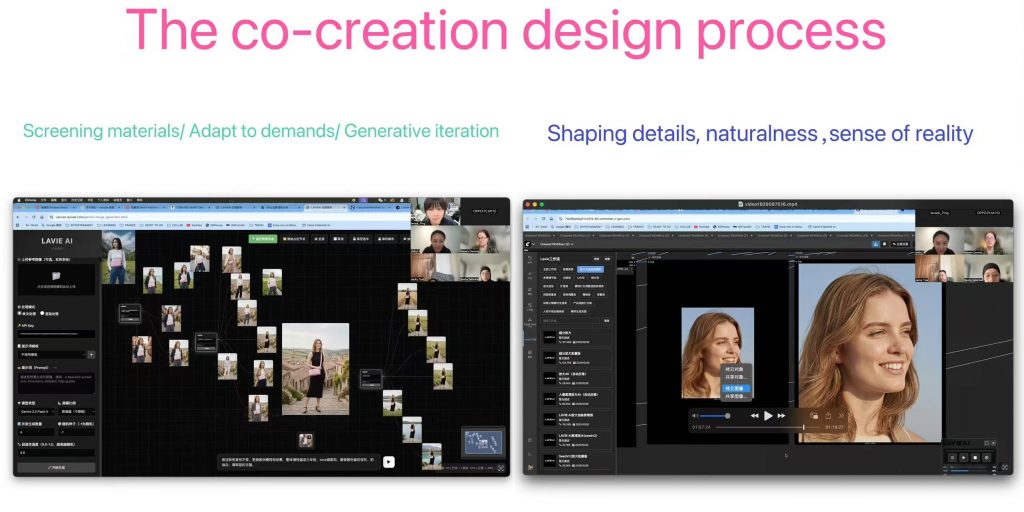

Both designers jointly screened and refined materials following the principles of authenticity and fidelity. The AI designer generated rapid scene integrations — iterating characters, poses, and styling — while the traditional designer focused on improving naturalness and realism.

The audience’s enthusiasm toward AI-driven creation continued to rise, and they expressed greater approval of the collaborative outputs.

Some participants, however, raised questions about copyright and market ethics, reflecting public concerns about authorship and transparency in AI design.

Phase 2 Summary:

Collaboration expanded creativity while reducing production cost, elevating both the strategic and emotional value of the brand.

The audience gradually shifted from passive receivers in a one-way communication model to active co-creators in a situational dialogue, strengthening their trust and emotional connection with the brand.

4 Methodology|Research Method

This study adopts Action Research as the methodological framework, using a comparative structure of Phase 1: AI vs. traditional independent creation and Phase 2: human–AI co-creation to observe differences in visual output within brand communication, and to record how collaboration affects audience emotion, trust, and brand connection.

The purpose of the experiment was not to determine “which is better,” but to explore the boundaries of AI creativity, the value of efficiency, how human warmth compensates for technology, and how emotional connection is triggered and transformed.

1) Data Collection

A total of 10 observers participated, and four types of data were collected:

| Data Source | Purpose |

|---|---|

| On-site behavioural observation | To judge attention, engagement depth, and discussion intensity |

| Real-time verbal feedback (Live Reaction) | To capture curiosity, surprise, skepticism, emotional distance, etc. |

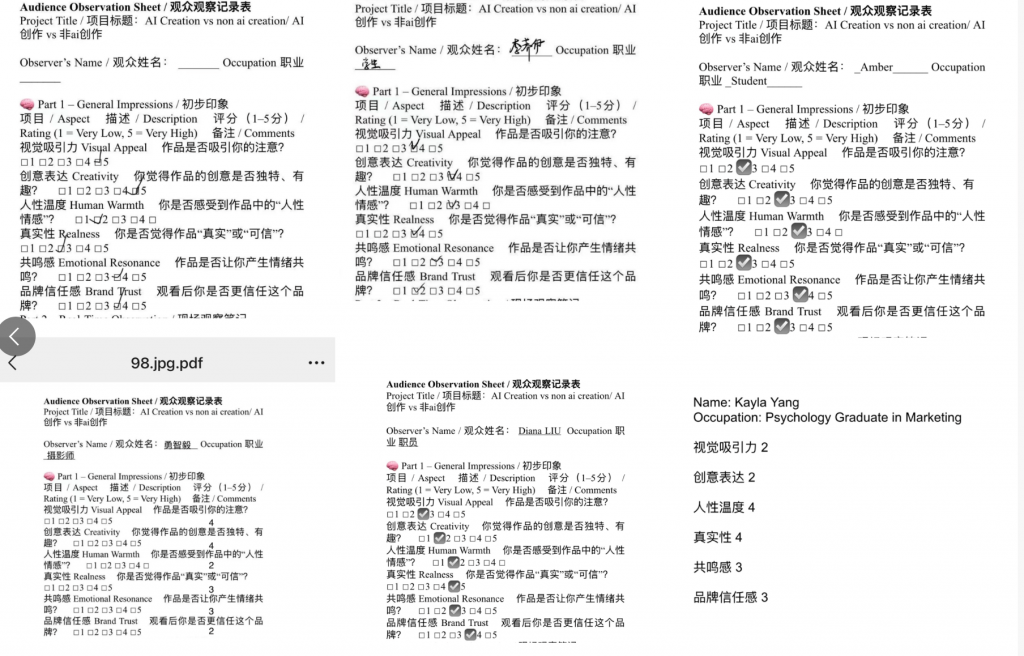

| Small-sample questionnaire (n=10) | Exploratory quantitative measurement of emotional resonance, authenticity, trust |

| Post-discussion and follow-up interview | To further understand copyright concerns, AI boundaries, and views on authorship |

Note: The sample size is small, therefore quantitative results are exploratory and used for trend indication rather than statistical inference.

2) Analysis Approach

This research applies a qualitative-dominant, exploratory-quantitative-supported mixed-method approach:

Qualitative Analysis

This project uses a qualitative-led, exploratory quantitative mixed-method approach, strengthened through triangulation across three data sources:

- Coding: breaking down interview phrases and marking meaning units

- Thematic Analysis: distilled six main themes

Efficiency / Warmth / Authenticity / Trust / Novelty / Attribution (effort = value) - Phenomenological Interpretation: focusing on experiential meaning rather than results alone

- Comparative Qualitative Analysis: comparing AI vs. human | independent vs. co-creation in creativity and emotional response

- Triangulation : Observation × Verbal feedback × Questionnaire trends cross-validated each other, enhancing reliability and interpretive confidence

Qualitative insights form the foundation, and quantitative signals act as supporting trend evidence, not statistical proof.

3) Interpretation Logic

A layered emotional connection path emerged through the comparative experiment:

AI attracts attention → interaction occurs → users join iteration → meaning and effort are perceived → trust and connection form

AI initiates and generates surprise.

Humans calibrate and provide warmth.

Co-creation becomes the mechanism through which interest transforms into emotional connection.

5 Reflection

Grounded in brand visual communication, this intervention demonstrates that, when aligned with audience and strategic insights, AI can become a powerful technological tool for brands, enhancing creative expression while reducing production time and cost.

It satisfies audience curiosity and entertainment while introducing new forms of brand interaction.

Throughout the experiment, audiences evolved from spectators to co-creators of meaning with brands, designers, and AI.

This prompted reflection on whether brand value should move beyond mere transmission — using AI to reshape the traditional relationship between brands and audiences, and build a new ecosystem that feels warmer and more personalized.

5 Feedback, Return Visit & Generalization

- Audience Observation Table –Analysis

| Scene | Facial Expression / Behavior | Feedback Keywords | Theoretical Mapping |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI designer generated 4 images in 1 minute | Sasha appeared excited; Robert asked about the software | “Efficiency,” “Surprise,” “Curiosity” | Curiosity Gap (Loewenstein, 1994): cognitive stimulus from innovation |

| Traditional designer image-cutting phase | Audience laughed, relaxed | “Familiarity,” “Human touch,” “Warmth” | Attribution theory (Heider, 1958): effort = perceived value |

| AI-generated video demonstration | Professional photographer praised the realistic details | “Efficiency,” “Potential” | |

| Artist’s closing remark | Serious tone, emphasized “AI as assistance” | “Boundary,” “Human authorship” | |

| Sasha’s final comment | “AI is efficient but lacks emotional connection” | “Warmth,” “Ethics”,”too perfect” | Uncanny Valley (Mori, 1970) |

- Audience perceptions – Analysis

The comparative analysis of audience perceptions across creativity, attractiveness, authenticity, emotional warmth, and trust revealed no statistically significant differences between AI-generated and human-created visuals.

- Audience Real-time Feelings – Analysis

Efficiency and Authenticity

- AI technology has greatly accelerated production workflows and expanded creative possibilities.

- Both AI and human-created visuals tended to appear realistic, suggesting a shared visual authenticity.

Emotion and Trust

- The value of creativity lies in humanistic care, critical reflection, and emotional warmth.

- According to Attribution Theory (Heider, 1958), people tend to assign higher value and emotional depth to outcomes perceived as the result of human effort and intention.

- Audiences reported that understanding the creative logic and process behind the brand evoked a stronger sense of respect and trust.

Collaboration and Future Outlook

- Audience attention and discussion largely focused on the AI side, but with no apparent resistance — indicating high acceptance.

- The integration of AI with brand outputs offered greater creative freedom and adaptability, such as dynamic and video-based presentation.

- Humans serve as the strategic and cultural lead, while AI acts as an efficient technical tool, supporting creative exploration and balancing emotional and technical values.

- When audiences observed or even participated in brand generation, AI became a multidimensional bridge between brands and people, enabling new forms of shared creation.

- Copyright and authorship issues were frequently raised by participants. Many expressed concern about the lack of clear ownership and transparency in AI-generated work. They suggested that future brand collaborations should establish transparent ethical frameworks to define human–AI contribution boundaries, ensuring credibility and creative accountability.

6 Weaknesses

This intervention was conducted entirely online via screen sharing.

While convenient, it limited real-time interaction and facial observation.

The sample size was small, and quantitative data were not statistically distinctive.

The experiment focused mainly on visual communication, which made the format slightly one-dimensional and lacked a systematic evaluation of copyright and market regulations — an area that requires further research and clarification.

References

Heider, F. (1958) The Psychology of Interpersonal Relations. New York: Wiley.

Loewenstein, G. (1994) ‘The psychology of curiosity: A review and reinterpretation’, Psychological Bulletin, 116(1), pp. 75–98. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.116.1.75.

Mori, M. (2012) ‘The uncanny valley’, IEEE Robotics & Automation Magazine, 19(2), pp. 98–100. Translated from Mori (1970) by K.F. MacDorman and N. Kageki. doi:10.1109/MRA.2012.2192811.

Leave a Reply