1.Theme– AI Jewelry Co-creation

In my previous interventions, I observed that when AI directly generates faces or human figures, participants often experienced authenticity doubts, uncanny valley reactions, and ethical discomfort.

Therefore, I shifted my focus to jewelry as a design carrier — it is tangible, avoids identity and bodily ethics issues, and naturally embodies emotion, aesthetics, and self-expression.

Theme of this intervention:

An Experimental Intervention Using AI-Personalized Jewelry Design to Examine Affective and Relational Brand Responses

The entire experiment included four main phases:

- Brand Encounter – Introducing participants to the brand’s emotional atmosphere.

- Personal Input – Translating participants’ identities, emotions, and preferences into prompts.

- AI Co-Creation – An AI designer generated personalized works in real-time, allowing participants to become co-creators.

- Emotional Reflection – Gathering emotional feedback through discussion and questionnaires to evaluate affective connection and brand relationship shifts.

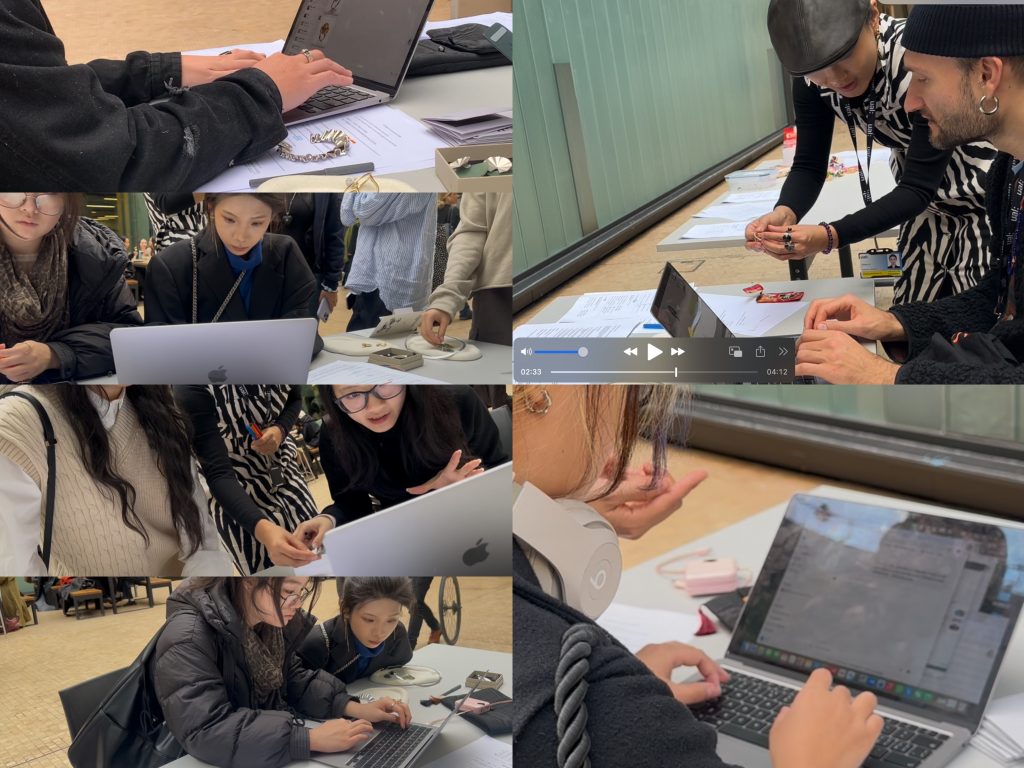

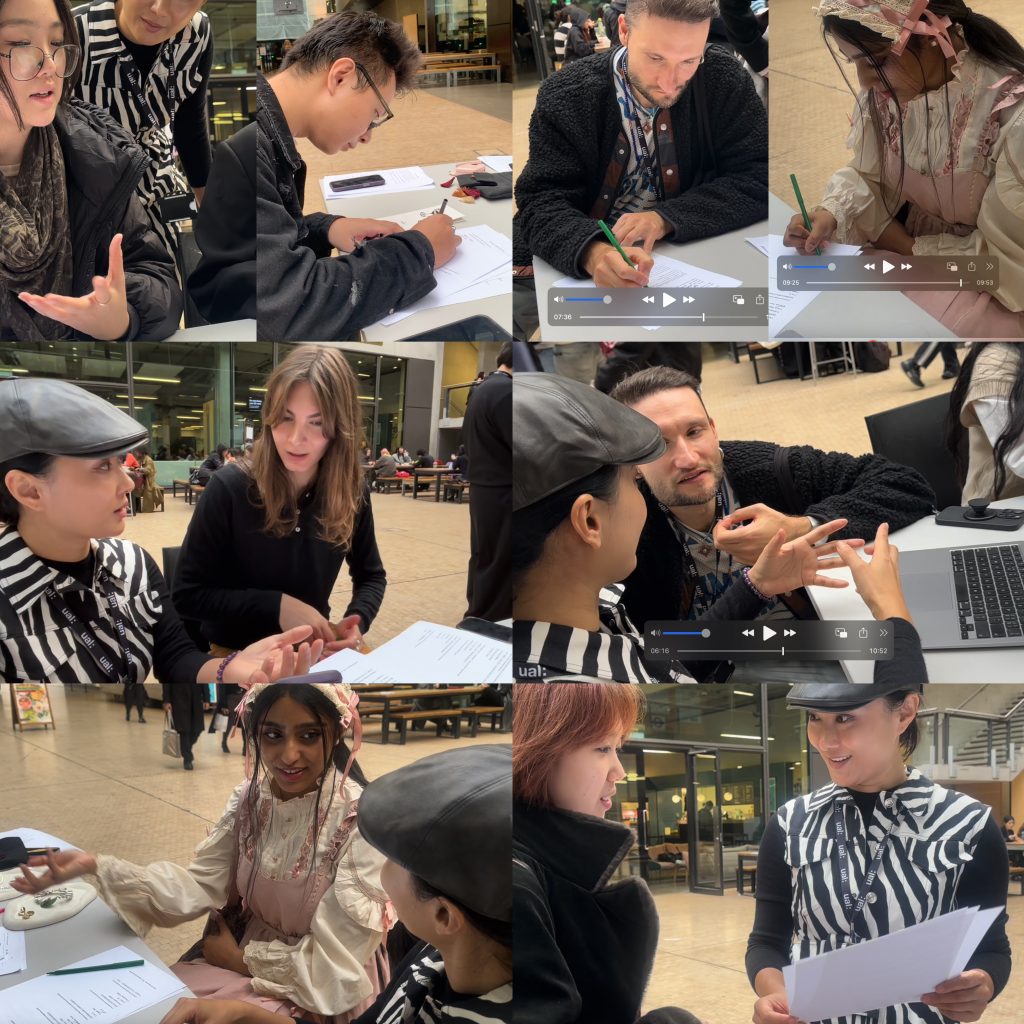

Participants: One AI designer, one host, one assistant, and 15 on-site participants.

Participants were voluntarily recruited from CSM Street, including students, visitors, and staff from diverse cultural and professional backgrounds (aged 18–40, from Europe, Asia, and other regions).

All participation was voluntary and anonymous; data were collected solely for academic purposes.

2. Intervention Structure – Four Phases

Phase 1: Brand Encounter & Context Setup

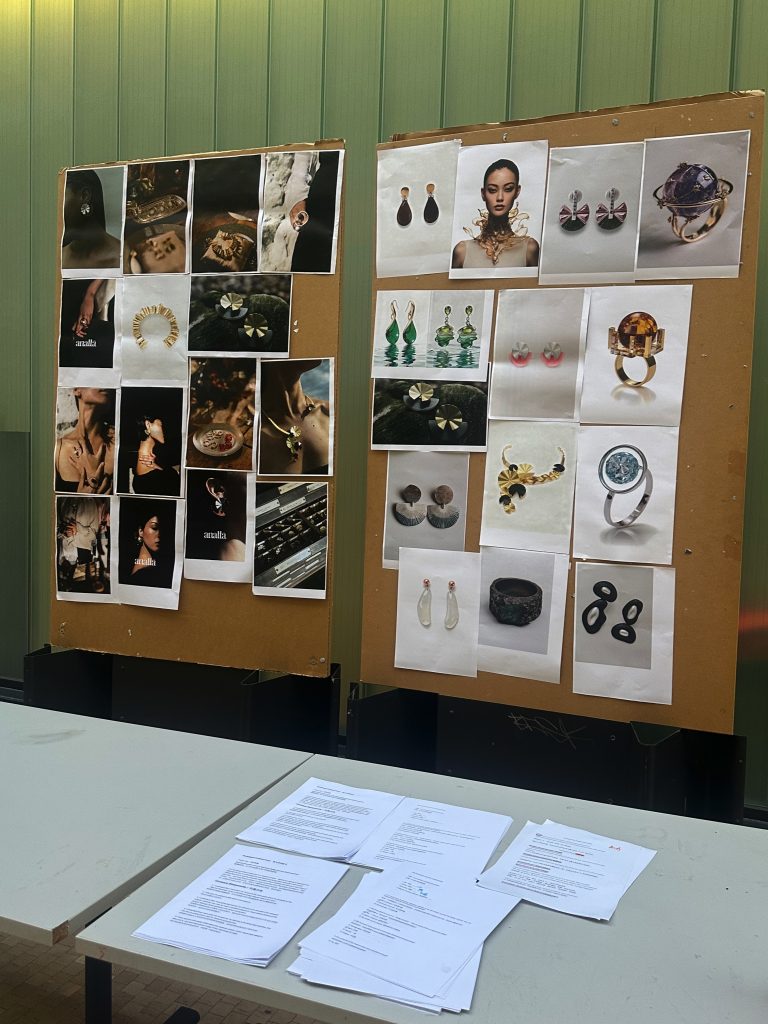

Participants entered the Anatta exhibition space at CSM Street.

They learned about the brand’s story, values, and aesthetic language, viewed jewelry samples and AI co-creation examples, and developed an initial emotional and aesthetic impression.

Objective: To build a preliminary affective bond between participants and the brand.

Reflection and conclusion

Feedback from the site indicated that participants entered with different motivations: some were drawn by visual displays and curiosity, others paused to ask questions and then left, while those who stayed were generally interested in the brand, the AI element, or the jewelry itself. Once this interest aligned with personal relevance, most participants were willing to engage further in the co-creation experiment, shifting from viewing to interacting.

It can indirectly indicate that the open brand exhibition space lowers the participation threshold and increases the possibility of connection with consumers/audience/even marginalized groups. Visual appeal is undoubtedly an entry point, but what truly creates connections and interactions is the welcome of individual interests and the open space for personal expression..

Phase 2: Personal Input & Prompt Creation

elected jewelry ,input personal information ,followed by deeper conversation with Chatgpt

Participants selected one piece of jewelry and input personal information into ChatGPT — such as age, gender, and nationality — followed by deeper conversation describing their current mood, energy state, preferred color, texture, shape, and emotional expectations (e.g., “what they hope this jewelry can bring them”).

The AI transformed these personal elements into visual prompts for design generation.

Objective: To make self-expression the starting point of co-creation, observing how identity → emotion → design is transformed.

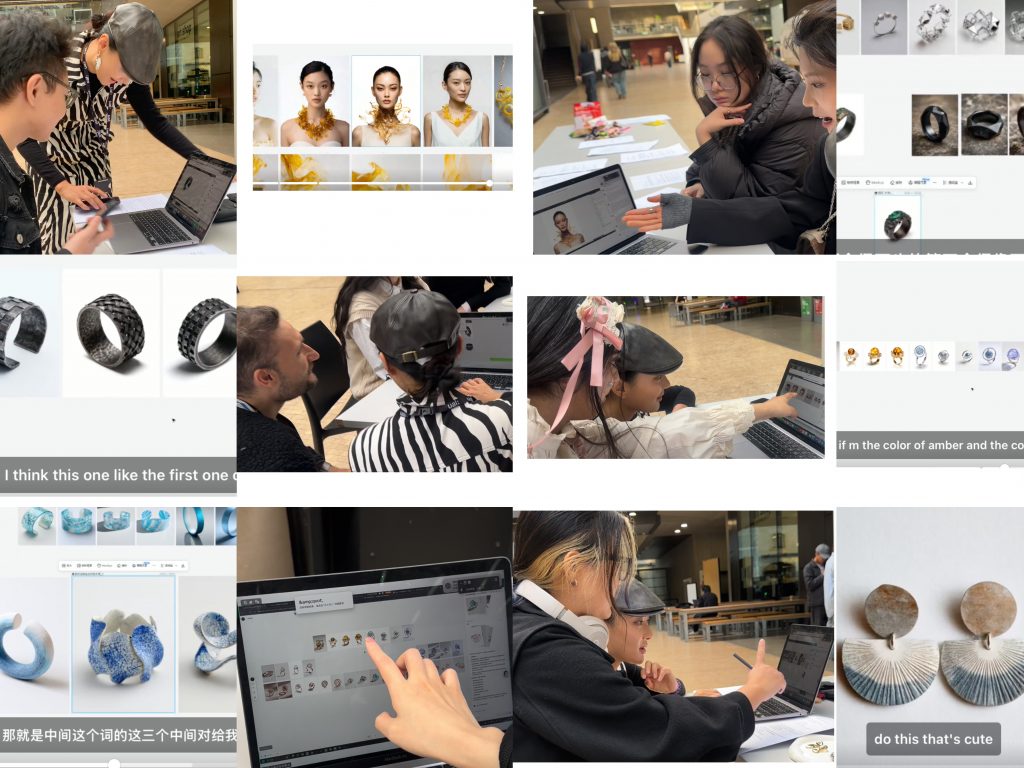

Reflection and conclusion The intervention stage shifted from brand presentation to personal expression. After selecting the piece of jewelry that they were most interested in or liked, participants engaged in a progressive dialogue interaction with ChatGPT based on their personal identity and emotions towards the selected jewelry – some relied on the AI to help them clearly express their thoughts, while others preferred to directly describe themselves. When the results were not satisfactory, they would adjust and re-set the prompts; when unexpected results occurred, the interaction became relaxed and interesting, full of exploratory nature. Through this iterative process, the user profile was deeply depicted, and the users’ tendency demands based on the selected products were also explored.

As the core driving force, with the premise of initiative, AI can expand imagination, but it may also deviate from expectations, prompting participants to adjust, negotiate, and regain creative rights. The final design outcome is no longer just a product, but a transformation chain from identity → emotion → language → visual form, and the emotional connection gradually forms through continuous shaping and response.

Phase 3: AI Co-Creation & Visual Output

An online AI designer used professional generative models (2D / 3D / motion graph) to create original jewelry visuals based on each participant’s prompt.

Participants could request further modifications (color, gloss, form, atmosphere, etc.).

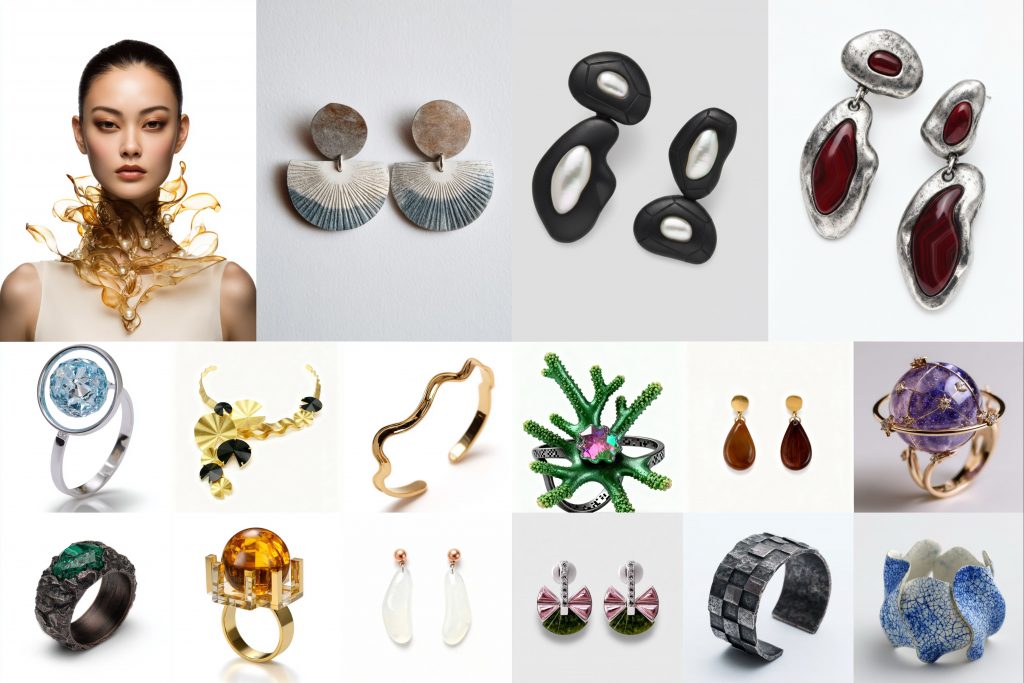

After several iterations and selections, each personalized design was finalized, printed, and added to the AI Co-Creation Wall.

Here is the video recording of the iteration and selection process

Here are the final selected jewellery designs,including photos and videos

Here are the participants’ reactions to the AI co-creation jewellery.

Here is the AI Co-Creation Wall

AI Co-Creation Wall

Objective: To test whether AI, through instant feedback and controllable modification, could enhance participants’ sense of being understood, emotional projection, belonging, and brand connection.

Reflection and conclusion

During the output stage, the assistance of artificial intelligence significantly enhanced the participants’ immersion and satisfaction. Some participants achieved the desired results on their first attempt and praised the artificial intelligence designers for their speed, efficiency, and effectiveness. Others found that the initial output differed from their expectations, so they continuously improved through discussions, additional prompts, or multiple systematic iterations. This repeated communication not only enhanced the final visual effect but also stimulated new creativity – some participants even shifted from two-dimensional graphics to dynamic graphics and believed that the video format showcased more details and realism.

The initial reactions were often immediate and emotional: “It’s natural, great, so amazing – I love it.” / “It’s cute.” / “It’s beautiful.” / “The video version is better – I can see the details.”

These feedbacks indicate that immediate feedback and controllable modifications help participants establish a closer connection with the design, thereby enhancing their sense of ownership and personal attachment.

Overall, artificial intelligence collaborative creation enhances creativity and efficiency, and also makes it easier for participants to reach innovations based on the brand. Belongingness and spiritual empowerment do not form instantaneously in the output of results, but are generated and firmly established in the cycle of “expectation → observation → adjustment → finalization”. The connection between the brand and the participants is further strengthened through guidance, selection (decisions), emotions, and personalization – transforming the digital generation process into an emotional, memorable brand experience.

Phase 4: Reflection, Sharing & Emotional Feedback

After viewing the final designs, participants shared their overall impressions of the entire experiment. We then further discussed the role of AI within the design process, whether they would be willing to participate in similar brand activities again, and whether AI co-creation enhanced their sense of connection with the brand.

After the discussion, they completed questionnaires assessing emotional resonance, trust, and brand bonding, and their works were featured in a Digital Gallery https://manatee-caper-2tn6.squarespace.com/.

Objective: To collect affective responses and experiential data to evaluate whether AI co-creation strengthens customer–brand emotional connections.

Discussion Analysis – What participants said

Novelty & Efficiency

- “It’s a new experience.”

- “AI’s fast and perfect generation was surprising.”

- “Unexpected — first time I liked an AI creative work.”

- “喜欢这个材质,很可爱。”

→ 人工智能的即时性和易用性是情感价值的关键来源。

Personalization & Feeling ‘Seen’

- “Individual experience, customized.”

- “Unique style depends on description.”

- “Having my design that I have described.”

- “参与设计过程感觉很有意义。”

→ 个性化不仅仅是一项功能,更是一种情感体验。

Attitudes toward AI and Human Roles

- “AI has emotional distance.”

- “Real designer fix.”

- “Prefer human crafts.”

- “Communication with real human assistant is important.”

→ AI was seen as efficient, but warmth and trust still came from human presence.

Brand Bonding

- “Using this as a tool to get customers’ attention is okay.”

- “This activity creates a positive connection.”

- “As a new brand, this is a good way to connect.”

- “Would consider buying if the real product matches.”

- → 人工智能协同创作被认为是一种有效的品牌互动方式。

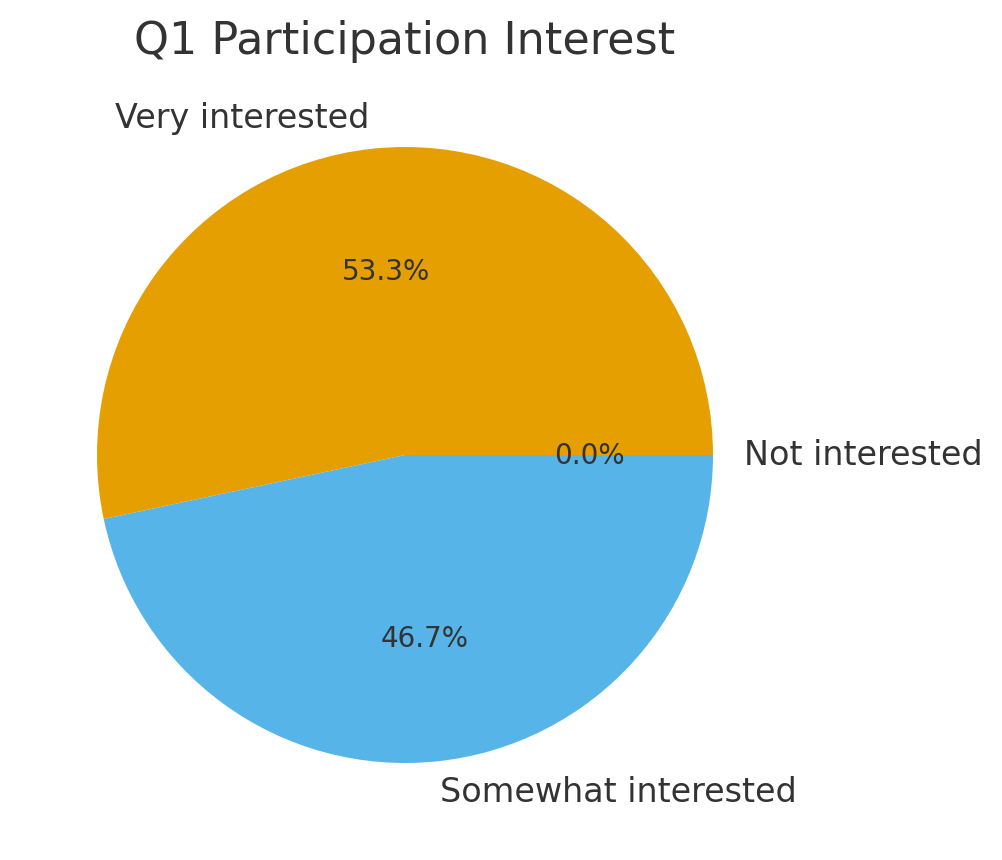

Questionnaire Analysis

- Interest in participation (Q1)

- Very interested: 8

- Somewhat interested: 7

- Not interested: 0

→ 100% showed interest — proving the high appeal of AI × self-expression × instant feedback.

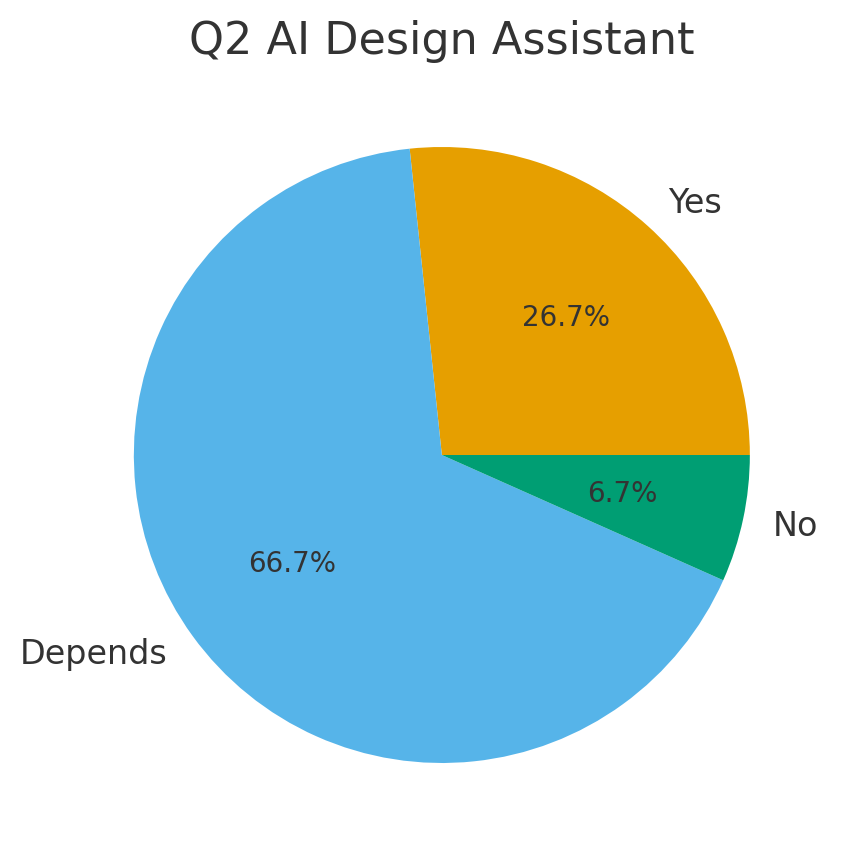

2. Willingness to use AI as an assistant (Q2)

- Strongly yes: 4

- Depends: 10

- No: 1

→ Most participants were open to AI collaboration but preferred retaining decision control.

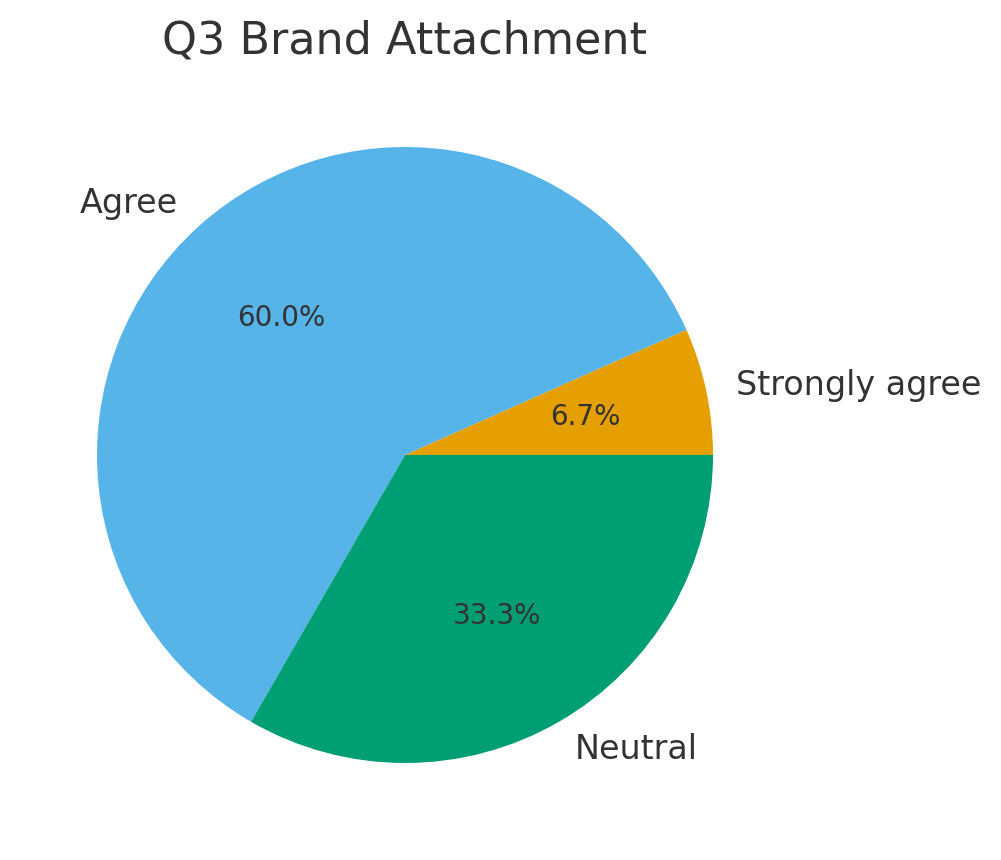

3. Emotional attachment to brand (Q3)

- Strongly agree: 1

- Agree: 9

- Neutral: 5

→ 66.7% reported stronger emotional attachment post-intervention — confirming AI co-creation as an effective branding tool.

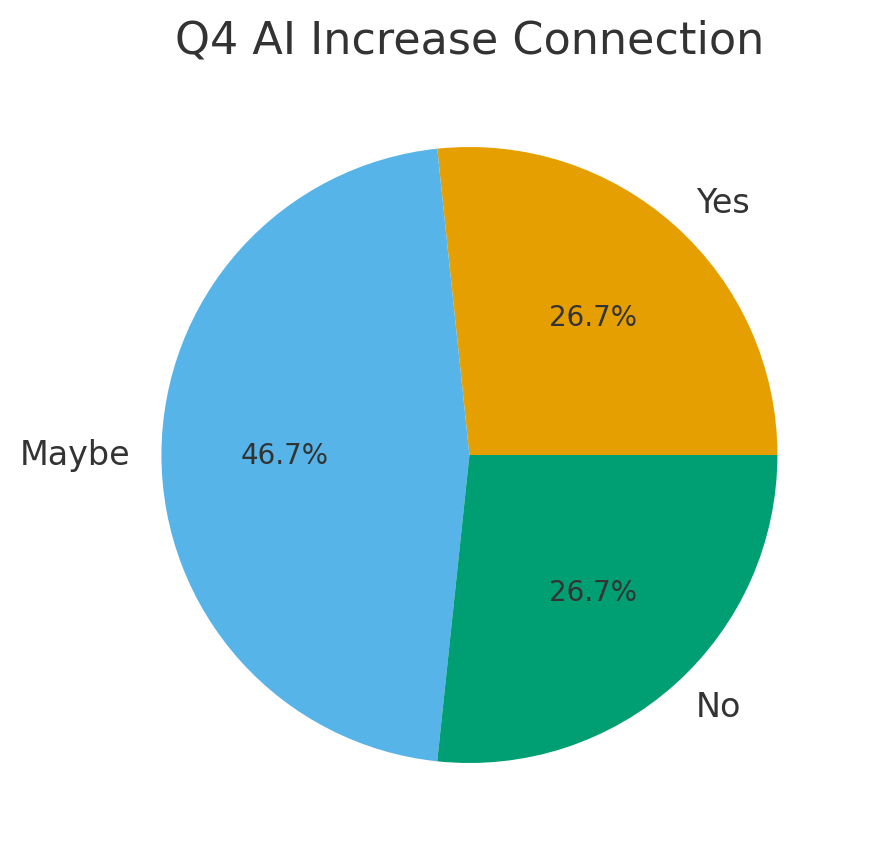

4. Feeling more connected to brand (Q4)

- Yes: 4

- Not sure: 7

- No: 4

→ The effect was conditional — AI creates potential for connection but doesn’t guarantee it.

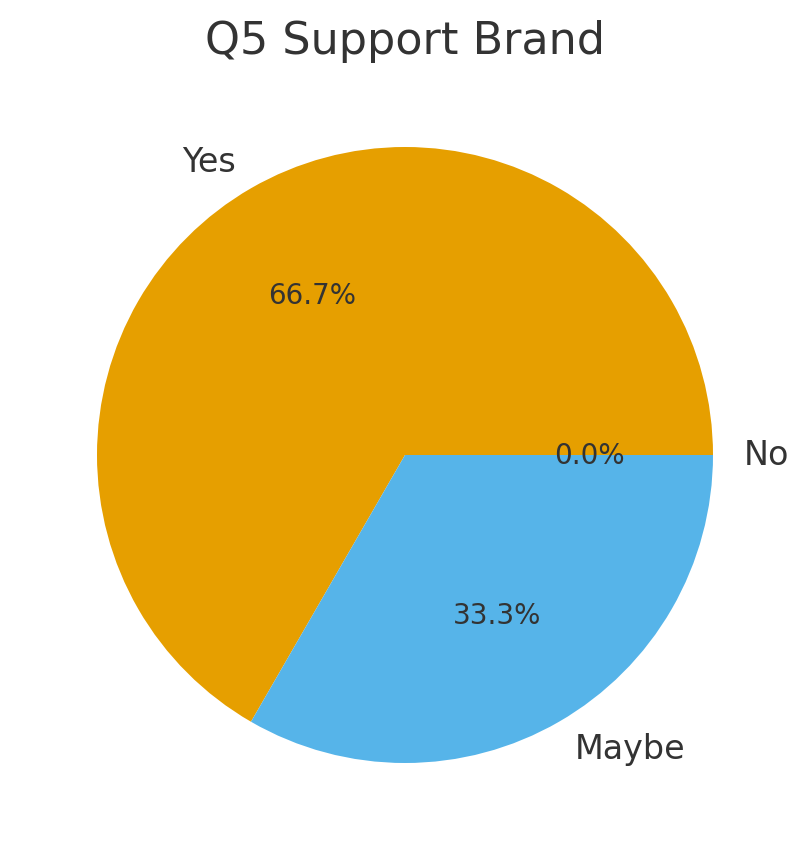

5. Willingness to follow/support the brand (Q5)

- Yes: 10

- Not sure: 5

- No: 0

→ Co-creation significantly enhanced brand friendliness and engagement.

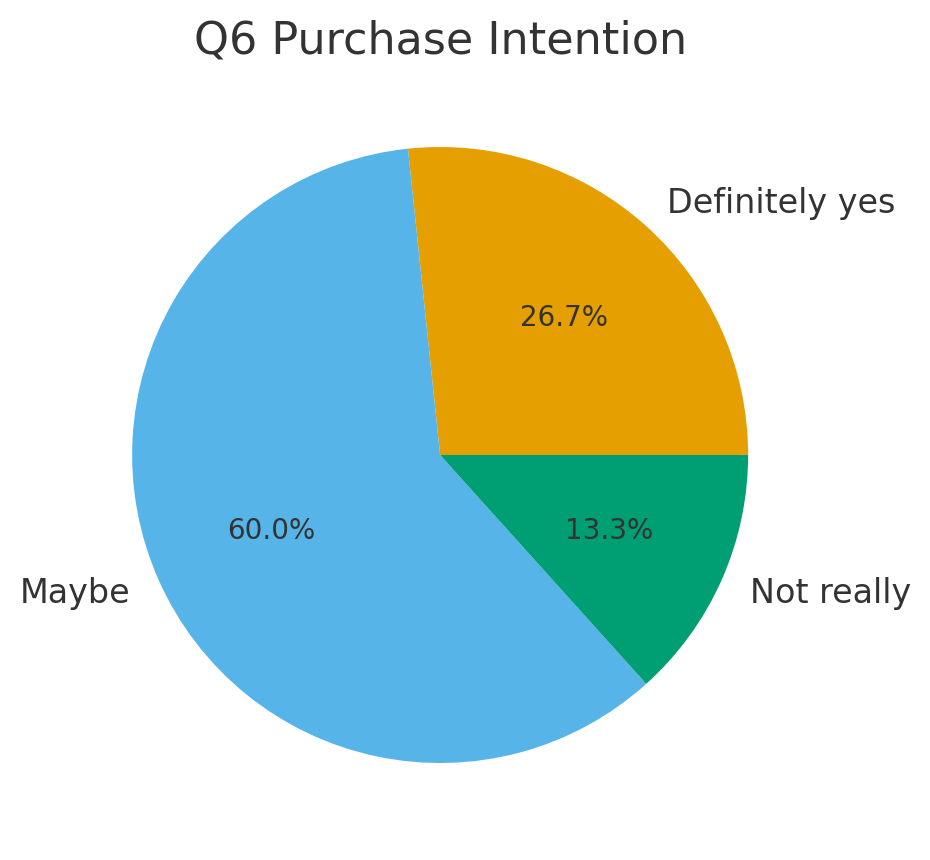

6. Purchase intention (Q6)

- Definitely would: 4

- Possibly: 9

- Unlikely: 2

→ The consistency between AI output and the physical product directly influences purchase conversion.

7. Willingness to share (Q7)

- Would share: 7

- Unsure: 6

- Would not: 2

→ The co-created visuals had strong social media sharing potential.

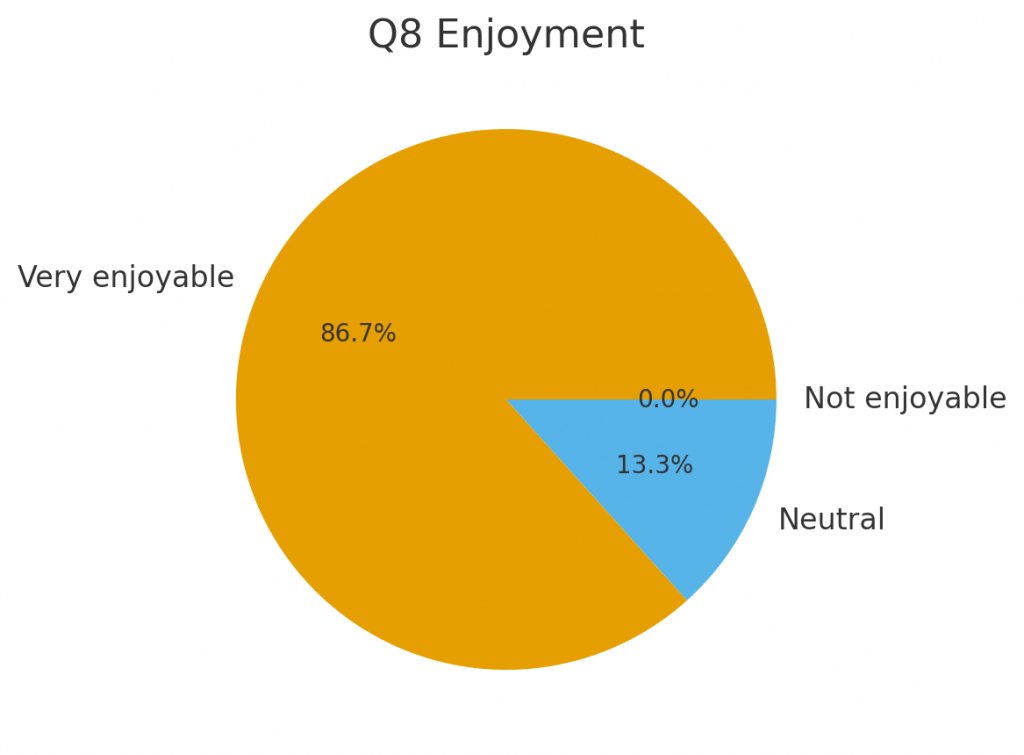

8. Enjoyment (Q8)

- Very enjoyable: 13

- Neutral: 2

- Not enjoyable: 0

→ Almost no negative experience — proving the format’s suitability for brand engagement.

反思与结论

The results of this stage show that AI co-creation significantly increased participants’ interest and willingness to engage. Novelty and rapid generation made the experience light, enjoyable, and low-barrier. However, emotional connection did not occur instantly — instead, it gradually formed only when participants’ expressions were acknowledged, when outputs aligned with inputs, and when human support remained present throughout.

Interviews reveal that AI’s value lies in speed and visual imagination, while emotional warmth and trust still rely heavily on the human role. When the final work successfully matched participants’ descriptions, it created a sense of being understood and being seen. When results diverged, participants re-entered and revised input, and this back-and-forth negotiation between human and machine became the very space where emotional connection took shape. The questionnaire echoes this — 66.7% reported increased brand closeness, and both purchase and follow-up intention improved, yet connection remained conditional, indicating that AI holds potential but emotional relationships still require construction.

Therefore, this study confirms: AI can enhance emotional connection between brand and consumer, but it acts more like a spark rather than the flame itself.

It ignites interest, offers speed and surprise, while true trust and belonging arise from co-creation, meaning-making, and the presence of human warmth. Future strategies should focus on improving output consistency, refining feedback structures, and maintaining human involvement to support the transition from enjoyable experience → emotional connection → brand loyalty.

3 Analytical Model

This research adopts an Action Research approach, progressing through cycles of design → execution → reflection → iteration.

The methodology consists of three components: data collection, analytical approach, and interpretive logic.

1) Data Collection

| Method | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Observational Behaviour | Recorded participation styles, iteration depth, dwell-time, exit points |

| Semi-structured Self-report Interviews | Captured emotional responses, attitudes, trust and experiential feedback |

| Questionnaire (n=15) | Quantitatively measured emotional resonance, brand affinity, purchase intention |

| Digital Gallery Archiving | Preserved generated works for traceability, review, and third-party validation |

2) Analysis Approach

This study applies a mixed-method analytical structure, combining qualitative and quantitative evidence:

| Analytical Method | How it was applied |

|---|---|

| Coding | Segmenting raw speech into meaning units |

| Thematic Analysis | Themes derived: Novelty / Personalization / Attitude/ Branding |

| Phenomenological Interpretation | Focus on feeling understood, being seen, meaning-making |

| Framework Comparison | Cross-examined four phases + behaviour × interview × survey data |

| Mixed-method Triangulation | Observation × Interview × Questionnaire → strengthened validity |

3) Interpretation Logic (Analytical Model)

The findings reveal a progression in the development of emotional connection:

Identity → Emotional Input → AI Output → Iteration → Ownership → Brand Connection

AI ignites interest → iteration generates emotional connection → human presence sustains trust.

4 Overall Reflection

This stage achieved multi-source triangulation, in which qualitative interviews revealed emotional experience, quantitative questionnaires provided structured measurement, and behavioural observation ensured the authenticity of participation. Follow-up stakeholder interviews further reinforced the findings, increasing the reliability and replicability of the interpretation. Through this multi-layered validation process, the research not only captures immediate affective responses but also maps how emotional connection emerges, offering a transferable framework for future studies on AI co-creation and brand relationship building.

The CSM Street intervention lasted four hours, during which countless micro-connections emerged. The activity illuminated the psychological, emotional, and social factors shaping consumer behaviour, enabling brands to deliver experiences that exceed transactional value. Overall, the intervention highlights AI’s potential to initiate emotion, while also revealing its limitations in sustaining emotional relationships. A platform that enables identity expression and facilitates ongoing relationships between consumers and brands via social media (Roggeveen et al., 2021), while remaining open and trustworthy, can be highly effective. An ideal, long-term narrative space can cultivate loyalty and belonging. Therefore, I decided to build a brand-AI creative linkage platform to continuously collect, exhibit, and update AI-generated brand creations, enabling real-time engagement for both participants and brands.

5 Limitations

Despite the intervention’s success in triggering immediate emotional responses, several limitations remain:

- Sample bias — Participants (n=15) were primarily art and design students, whose heightened aesthetic sensitivity and curiosity may have skewed the results towards more positive experiences.

- Context dependency — The intervention relied heavily on contextual design, researcher facilitation, and human–AI collaboration, making it difficult to isolate the pure emotional effect of AI alone.

- Lack of physical verification — Outputs existed only digitally, without tangible qualities such as weight or craftsmanship, meaning participants could only rely on human designers for validation.

- Time constraints — As a one-off experience, the data primarily captured immediate emotional reactions, not long-term emotional bonds.

Future work should involve iterative testing and comparative studies across diverse contexts to examine AI-assisted co-creation’s long-term emotional and relational effectiveness within brand building.

Reference

A.L. Roggeveen, D. Grewal, J. Karsberg, S.M. Noble, J. Nordfalt, V.M. Patrick, E. Schweiger, G. Soysal, A. Dillard, N. Cooper, R. Olson, Forging meaningful consumer–brand relationships through creative merchandise offerings and innovative merchandising strategies, J. Retailing, 97 (1) (2021), pp. 81-89, 10.1016/j.jretai.2020.11.006

Leave a Reply